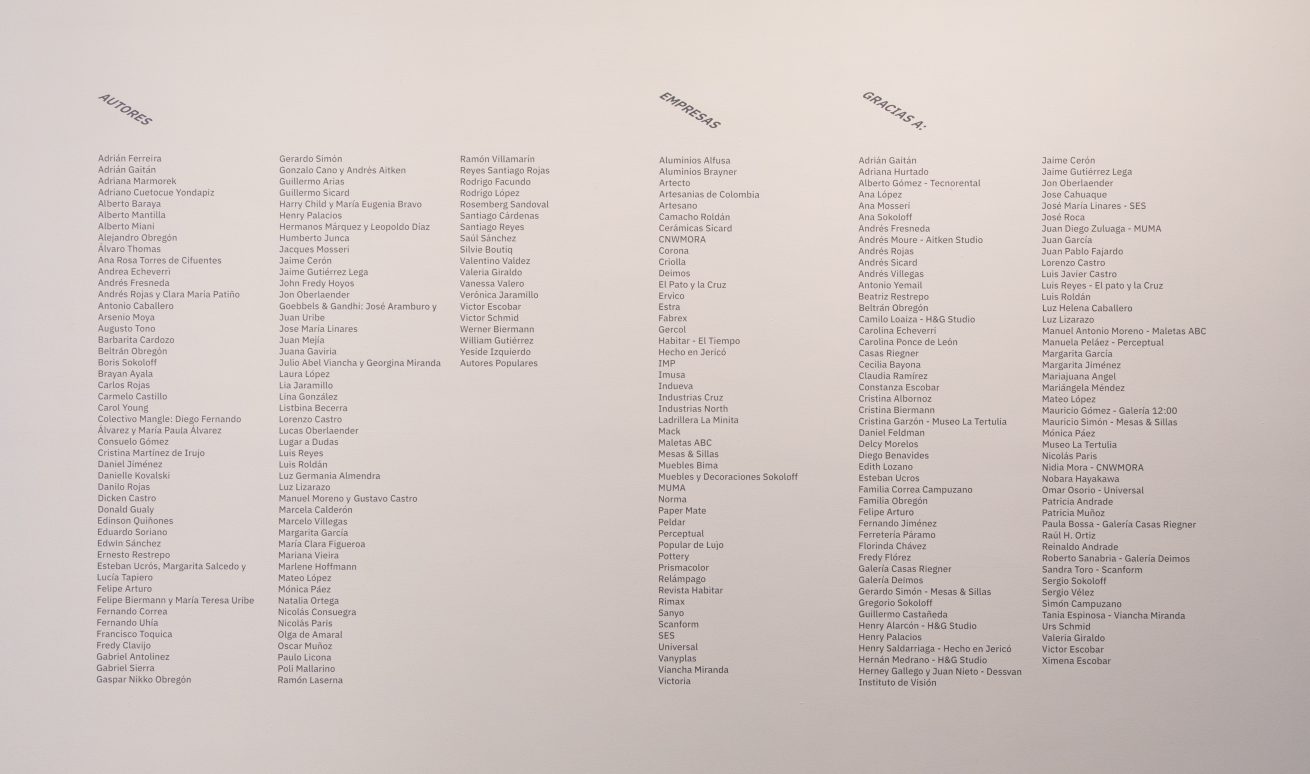

Proyecto ganador de la Beca de programación en artes plásticas Red Galería Santa Fe 2019.

Del 14 de noviembre de 2020 al 14 de febrero de 2021.

“No es infrecuente, en las regiones más antiguas de Tlön, la duplicación de objetos perdidos. Dos personas buscan un lápiz; la primera lo encuentra y no dice nada; la segunda encuentra un segundo lápiz no menos real, pero más ajustado a su expectativa. Esos objetos secundarios se llaman hrönir y son, aunque de forma desairada, un poco más largos.”

—Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.

En 1959 el Club de Profesionales de Medellín le encarga a Jaime Gutiérrez Lega una silla para el área de piscina. La silla debía resistir los rigores de la intemperie. No era un reto fácil considerando que en ese momento en Colombia no había producción industrial de plástico ni mucho menos plástico termoformado. La solución de Gutiérrez Lega fue sorprendente: una estructura simple de varilla de hierro doblada y soldada de forma tal que soportara un neumático inflado; materiales fáciles de conseguir y de ensamblar tanto a escala industrial como artesanal. La silla además era fácil de reparar y mantener, y sus materiales completamente reciclables. Todo esto en un momento donde estas cuestiones no estaban siquiera en el horizonte. El diseño de Gutiérrez Lega no se puede reducir solamente a su eficacia y precisión. Hay algo que amarra los dos elementos, neumático y varilla de hierro y los convierte en una cosa inesperada, pero al mismo tiempo muy familiar. Como si fuera la respuesta obvia a un acertijo que nadie había resuelto. Tal vez es el neumático y su forma básica, que desde siempre ha invitado a ser usado de mil maneras distintas de su intención industrial. Un objeto sobre el que no es necesario pensar mucho, pero que está ahí, a la mano, propiciando usos, afectos y recuerdos.

Esta exposición es una revisión preliminar de un problema que la desborda: la cultura material doméstica en Colombia a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Una realidad propia basada en nuestros objetos, en cómo nos hemos relacionado con ellos y cómo se han implicado en nuestra vida cotidiana, cómo es y qué cosas la conforman. ¿Cómo se han producido? ¿Cuáles son sus patrones de uso? ¿Cuándo se desechan? ¿Cuándo se olvidan? ¿Qué gravita en torno a estos? Formas de pensar, ideas, ideologías, afecto, imaginación, poder y sobre todo las mil maneras en las que al ser usados transforman y son transformados. La relación con los objetos es compleja. Al mismo tiempo que los objetos domésticos propician con su uso cotidiano relaciones afectivas y subjetivas, no es posible negar que también señalan cambios en las formas de producción o en las políticas económicas. La silla de Gutiérrez Lega es un ejemplo, entre muchos, de esto. No se puede reducir al cálculo económico, o a las limitaciones históricas de los procesos de producción e industrialización en Colombia, o a los referentes culturales y afectivos de sus materiales o a la eficacia y precisión de su diseño. La silla contiene todos estos elementos, pero los desborda. Especialmente cuando alguien se sienta en ella y sonríe porque de alguna manera extraña, y a la vez íntima, la entiende.

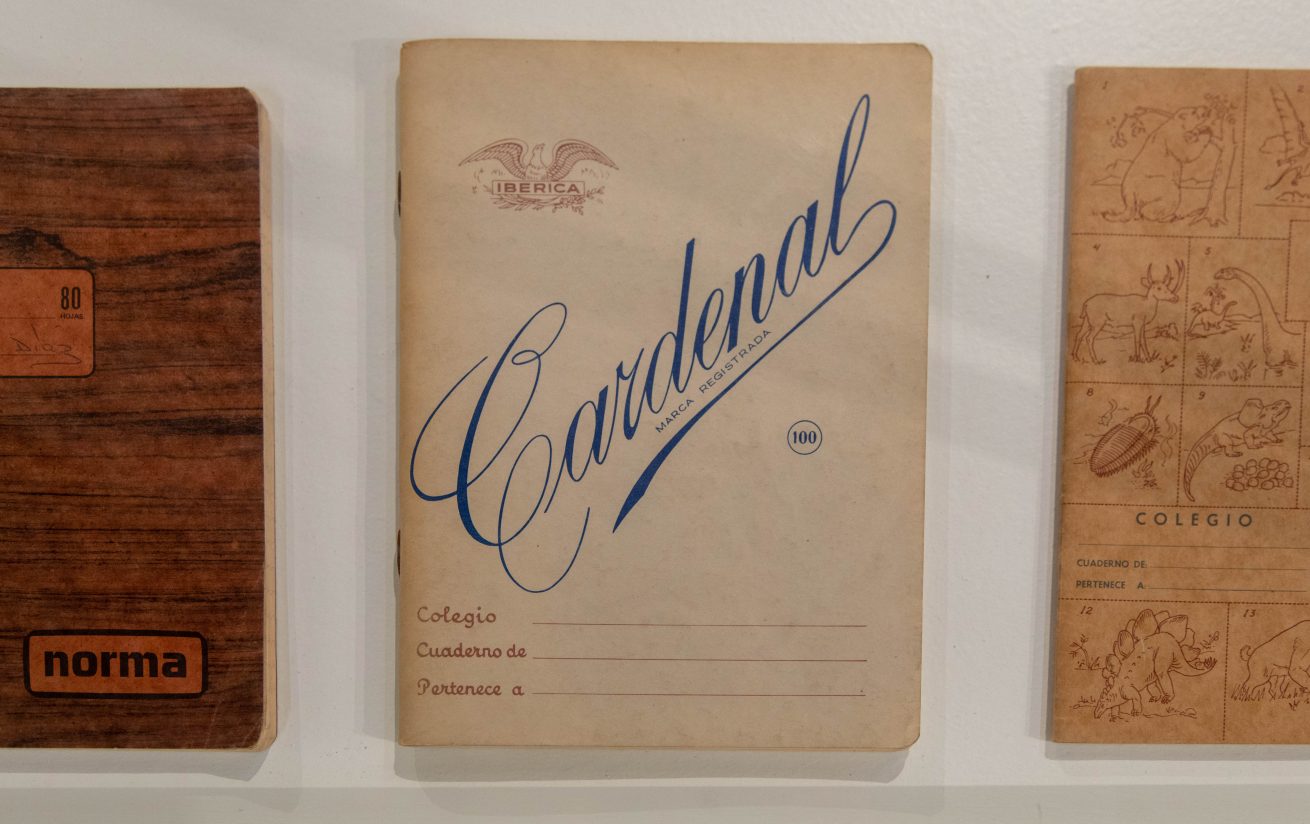

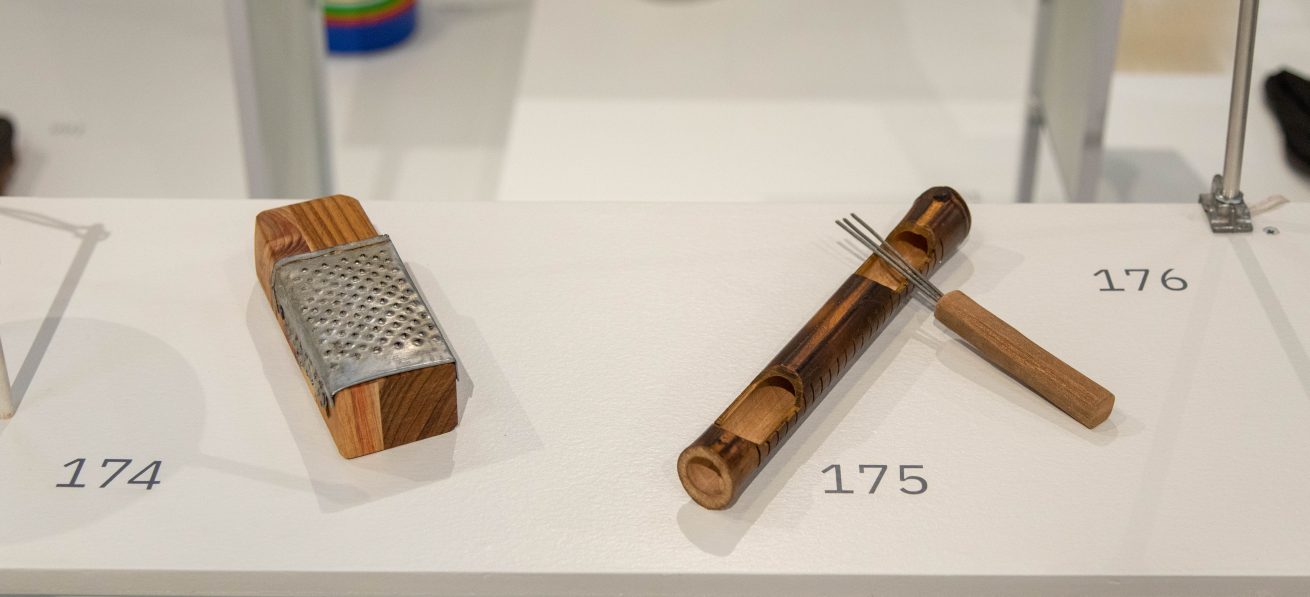

Una revisión de la cultura material doméstica idealmente debería dejar que sean las cosas mismas las que revelen lo que gravita en torno a estas, a su materialidad, sus procesos de producción, sus patrones de uso o a los afectos que suscitan. Sin embargo, lo que gravita en torno a los objetos no es un todo armónico, justo lo contrario, son cuestiones que muchas veces se contradicen o por lo menos tienen una relación ambigua o problemática entre sí. Los procesos de producción no se corresponden con los materiales o con la manera cómo algo es usado. Por ejemplo, para entender una lámpara hecha con bolsas plásticas, una silla Rimax fabricada en cera, una mesa plegable forrada en Con-Tact, un canasto hecho con papel impreso, cortado y trenzado, una media hecha colador de café o un bargueño hecho en Formica, es necesario desmontar cuidadosamente las capas que le dan sentido a estas cosas. Quizás evidencian un desarrollo industrial precario, pero ayudan a entender críticamente los procesos de modernización en Colombia: los intentos fallidos de industrialización y de desindustrialización, la convivencia permanente de modos de producción artesanales, semiartesanales, semindustriales e industriales y todos los modos híbridos que por su mera existencia ponen en aprietos las narrativas dominantes sobre el desarrollo y lo moderno. Lo doméstico es un escenario en el que el uso de las cosas se resiste de una forma casi natural a estas narrativas totalizadoras.

En 1976, después de convivir varios años con comunidades Nasa en el norte del Cauca, Álvaro Thomas publica su Tratado de la silla. Un libro con una tesis simple de enunciar, pero que nos permite entender de una forma concreta todo lo que gravita en torno a una cosa, en este caso una silla. Los nasa que conoció Thomas no usaban sillas porque su modo de vida propiciaba otras formas de sentarse, reunirse, comer, o trabajar. Y eso nos obliga a preguntarnos por nuestras formas de sentarnos, reunirnos, comer o trabajar. El libro de Thomas nos sirve como un contrapeso a la exposición porque repite incesantemente esas preguntas sobre nuestras formas de vida y de uso de las cosas.

La exposición está estructurada como un eje que recorre todos los modos de producción desde lo artesanal a lo industrial pasando por lo vernacular, lo semindustrial y sus híbridos. Los puntos que trazan este eje son sillas, desde un banco pensador hasta una Rimax. Mostrar el mismo tipo de objeto construido desde perspectivas tan diferentes invoca las preguntas por nuestras formas de vida y de uso de las cosas. Perpendicular a este eje hemos construido escenarios con otros objetos que profundizan en los interrogantes que el eje principal abre, revelando las capas afectivas, ideológicas o económicas que le dan forma o que por el contrario cuestionan la forma de las cosas.

Esto explica porque esta no es una exposición de diseño, ni de arte, ni de artesanía. Creemos que los rótulos disciplinares despojan a los objetos de sus posibilidades críticas y les obliga a quedarse en “su sitio”. Un objeto hecho artesanalmente puede ser un mordaz comentario sobre la relevancia de otro producido masivamente en plástico termoformado. La reproducción terca, meticulosamente artesanal, de un objeto común puede revelar la belleza de su forma que por ser tan ubicua pasa desapercibida. Es así que esta exposición no pretende contar ninguna verdad última sobre las cosas domésticas, más bien busca desplegar en el espacio la capacidad que ellas tienen para interrogar nuestras formas de vida y apropiarse de nosotros mismos.

Liliana Andrade

Bernardo Ortiz

José Sanín

Giovanni Vargas

Temporary department of objects

“In the most ancient regions of Tlön, the duplication of lost objects is not infrequent. Two persons look for a pencil; the first finds it and says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but closer to his expectations. These secondary objects are called hronir and are, though awkward in form, somewhat longer.”

—Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertuis.

In 1959, Medellín’s Club de Profesionales commissioned Jaime Gutiérrez Lega to design a chair for the pool area, one which could withstand the rigors of the elements. It was not an easy task, given that industrial plastic production, much less plastic thermoforming, didn’t exist in Colombia at the time. Gutiérrez Lega’s solution was surprising: a structure created from a simple iron rod, bent and welded in such a way that it supported an inflated inner tube—materials that were easy to procure and assemble, on both an industrial and artisan scale. The chair was also easy to repair and maintain, and its materials were completely recyclable. And here we’re are referring to a time when these matters were not even on the table. Gutiérrez Lega’s design cannot be reduced solely to its efficiency and precision. There is something that ties the two elements—inner tube and iron rod—together, making them into an unexpected creation, yet simultaneously very familiar, as if it were the obvious answer to a riddle that no one had solved. Perhaps it is the inner tube and its elemental shape that has so often inspired a use other than its industrial intention—an object that doesn’t ask for much, but is there, at hand, inciting novel uses, affection, and memories.

This exhibition is a preliminary review of a problem that spills over: the domestic material culture in Colombia during the second half of the 20th century. It’s a reality of our own creation, based on our objects, how we have related to them, and how they have been involved in our daily life—what it’s like and what things make it up. How have they been produced? What are their usage patterns? When are they discarded? When are they forgotten? What orbits around them? Ways of thinking, ideas, ideologies, affection, imagination, power, and above all, the thousand ways in which they transform and are transformed when used. Our relationship with objects is complex. While objects foster an emotional and subjective reaction through their daily use, it cannot be denied that they also point to changes in systems of production or economic policies. Gutiérrez Lega’s chair is just one of many examples. It cannot be reduced to economic calculation, or the historical limitations of production and industrialization processes in Colombia, or the cultural and emotional inspiration from its materials, or the efficiency and precision of its design. The chair contains all these elements, but it transcends them—especially when someone sits on it and smiles—because in some strange, intimate way, they understand it.

A review of domestic material culture should ideally let the things themselves reveal what orbits around them—their materiality, production processes, usage patterns, or the feelings they elicit. However, what orbits around objects is not a harmonic whole; on the contrary, they are issues that often contradict themselves or at least have an ambiguous or problematic relationship with each other. The production processes do not correspond to the materials or the way in which something is used. For example, to understand a lamp made from plastic bags, a Rimax chair made of wax, a folding table covered with Con-Tact paper, a basket made of cut and braided printer paper, a stocking made from a coffee strainer, or a vase made of Formica, it is necessary to carefully disassemble the layers that give meaning to these things. Perhaps they show a precarious industrial development, but they help to critically understand modernization processes in Colombia—the failed attempts to industrialize and de-industrialize, the permanent coexistence of artisanal, semi-artisanal, semi-industrial and industrial modes of production, as well as all the hybrid modes whose mere existence puts the dominant narratives on development and modernity in a bind. The domestic scene is one in which using things almost naturally resists these totalizing narratives.

In 1976, after living with Nasa communities for several years in northern Cauca, Álvaro Thomas published El Tratado de la Silla. His book has a simply stated thesis, but it allows us to understand, in concrete terms, everything that orbits around a thing—in this case, a chair. The Nasa that Thomas spent time with did not use chairs, because their way of life favored other ways of sitting, meeting, eating, or working, thus obligating us to examine our own ways of sitting, meeting, eating, or working. Thomas’s book serves to counterbalance the exhibition because it incessantly repeats these questions about our ways of life and the way things are used.

The exhibition is structured in a linear format that runs through all production modes, from artisanal to industrial to vernacular, semi-industrial, and its hybrids. The points that comprise it are chairs, from a thinking bench to the mass-produced Rimax plastic chair. Showing the same type of object constructed from such different perspectives invokes questions about our ways of life and the use of things. Tangentially, other objects are used to create scenes that further delve into the themes that the main axis touched upon, revealing the emotional, ideological, and economic layers that shape it or, on the contrary, question the shape of things.

This explains why this is an exhibition focused on design, not art or handicrafts. We believe that disciplinary labels strip objects of their critical possibilities and force them to stay “in their place.” A handmade object can be a scathing commentary on the relevance of another mass-produced thermoformed plastic object. The stubborn, meticulously handcrafted reproduction of a common object can reveal the beauty of its shape, which, being so ubiquitous, goes unnoticed. Thus, this exhibition does not intend to tell any ultimate truth about domestic things, but rather aims to physically display how domestic things are capable of questioning our ways of life and dominating us.

Liliana Andrade

Bernardo Ortiz

José Sanín

Giovanni Vargas